Case study: 52-Year-Old Male with Abdominal Pain-Acute Sigmoid Diverticulitis with Localized Microperforation (Uncomplicated)

Uncomplicated sigmoid diverticulitis with microperforation

1. Cause

Uncomplicated sigmoid diverticulitis with microperforation results from inflammation or localized infection of a colonic diverticulum, most commonly within the sigmoid colon. A microperforation refers to a tiny defect in the diverticular wall that permits limited extraluminal leakage of gas or luminal contents. This typically provokes a localized pericolic inflammatory response, which remains contained without progression to generalized peritonitis, due to effective confinement by adjacent mesenteric fat or the omentum.

2. Etiology

The development of

diverticulitis with microperforation is typically the result of:

- Luminal obstruction of a diverticulum (e.g.,

by fecaliths or inspissated stool)

- Elevated intraluminal pressure leading to mucosal

injury and bacterial overgrowth

- Localized ischemia, mucosal necrosis, and

ultimately microperforation

Contributing risk factors

include:

- Low-fiber Western diets

- Aging (due to muscular and connective tissue changes)

- Obesity

- Sedentary lifestyle

- Chronic constipation

- Use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

(NSAIDs) or corticosteroids

- Smoking

- Possible alterations in gut microbiota

(dysbiosis)

3. Pathophysiology

The pathophysiologic cascade

typically involves:

- Diverticular neck obstruction and increased

intradiverticular pressure

- Bacterial proliferation and local inflammation

- Microperforation through the diverticular

wall

- Leakage of minimal gas or inflammatory exudate into adjacent tissues

- Containment by surrounding

structures (pericolic fat, mesentery, omentum)

This leads to a localized

peritonitis without systemic sepsis or complications such as abscess,

fistula, or free perforation, distinguishing it from complicated

diverticulitis.

4. Epidemiology

- Diverticulosis affects over 50% of individuals

over age 60 in Western populations

- 10–25% of individuals with diverticulosis develop

diverticulitis

- Among these, 75–85% present with uncomplicated

disease

- Microperforation is detectable in

approximately 10–20% of diverticulitis cases on CT imaging

- The sigmoid colon is the most commonly

affected site

- Males are more affected before age 50, with female

predominance in older adults

5. Clinical Presentation

Typical signs and symptoms:

- Left lower quadrant abdominal pain (most common)

- Fever and chills

- Altered bowel habits (constipation or

diarrhea)

- Nausea and/or vomiting

- Mild to moderate abdominal tenderness (without signs of

peritoneal irritation)

- Leukocytosis and elevated C-reactive

protein (CRP)

Special considerations:

- Elderly or immunocompromised patients may present atypically

(e.g., absence of fever or leukocytosis)

- Generalized peritoneal signs should raise concern for

progression to complicated diverticulitis

6. Imaging Features

Contrast-enhanced CT scan of

the abdomen and pelvis is the diagnostic gold standard.

- Segmental colonic wall thickening (usually ≥4 mm)

- Pericolic fat stranding indicating localized

inflammation

- Presence of colonic diverticula

- Pericolic extraluminal air (hallmark of

microperforation)

- Small pericolic fluid collections may be seen, but should

not meet criteria for abscess

Findings that indicate

complicated diverticulitis (and exclude the "uncomplicated" label):

- Free intraperitoneal air

- Abscess formation (>3 cm)

- Fistulae

- Bowel obstruction

7. Treatment

Non-operative management is

standard for uncomplicated diverticulitis, including those with

microperforation.

In clinically stable patients:

- Bowel rest (clear liquids or NPO

initially, gradual reintroduction of diet)

- Oral antibiotics (7–10 days):

- Example: Ciprofloxacin + Metronidazole

- Or: Amoxicillin-clavulanate as monotherapy

Indications for inpatient

management:

- Elderly, immunocompromised, or high-risk

comorbidities

- Inability to tolerate oral intake

- Severe pain, fever, or leukocytosis

In these cases:

- IV fluids

- IV antibiotics (e.g., piperacillin-tazobactam,

or ceftriaxone + metronidazole)

- Analgesia (opioids preferred over

NSAIDs due to perforation risk)

Surgical intervention:

- Rarely required for uncomplicated cases

- Considered only if the patient fails medical therapy

or progresses to a complicated disease

8. Prognosis

- The prognosis is excellent with appropriate

conservative treatment

- Clinical improvement is typically observed

within 48–72 hours

- Full resolution within 7–10 days in most

cases

- Recurrence rate: 10–30%, though most

recurrences are mild and managed non-operatively

- Elective sigmoid colectomy may be considered for:

- Recurrent or refractory diverticulitis

- Persistent symptoms impairing quality of life

- High-risk anatomy or complications in past episodes

Surgical decisions are now

based on patient-specific factors rather than a fixed number of recurrences.

Guidelines

- American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) Clinical

Guideline: Management of Diverticulitis (2022)

- American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons

(ASCRS) Clinical Practice Guidelines

- Hinchey Classification for diverticulitis severity

- UpToDate: "Acute uncomplicated diverticulitis in adults"

Case study: 52-Year-Old Male with Abdominal Pain

Acute Sigmoid Diverticulitis with Localized Microperforation (Uncomplicated)

History and Imaging

-

A 52-year-old man presented with abdominal pain that had persisted for more than two days.

He denied any associated symptoms but reported experiencing similar episodes in the past.

His medical history was significant for two prior inguinal hernia repairs.

On physical examination, the abdomen was soft, with distension and tenderness localized to the left lower quadrant.

Vital signs were within normal limits, and laboratory studies revealed no significant abnormalities.

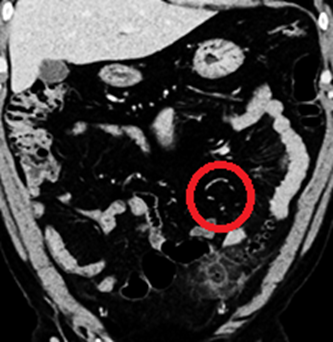

A contrast-enhanced CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis was performed for further evaluation.

Quiz

1. What is the key CT finding?

(1) High-grade bowel obstruction

(2) Microperforation

(3) Pneumoperitoneum

(4) Abscess

Explanation: Of the options listed, microperforation is the sole finding demonstrated on the CT scan. There is no radiologic evidence of bowel obstruction, free intraperitoneal air, or abscess formation.

2. What is the underlying pathophysiology of this diagnosis?

(1) Increased intraluminal pressure due to erosion of the diverticular wall by food particles

(2) Torsion of an extraperitoneal adnexal structure

(3) Mechanical bowel obstruction due to adhesions

(4) Vascular injury to the omental and mesenteric blood supply

Explanation: Based on the CT findings and clinical history, the presumed pathogenesis involves increased intraluminal pressure resulting in erosion of the diverticular wall by impacted food particles or stool, leading to localized inflammation and microperforation.

3. What is the most likely diagnosis?

(1) Acute uncomplicated diverticulitis

(2) Acute complicated diverticulitis

(3) Intra-abdominal appendicitis associated with asymptomatic diverticulosis

(4) Small bowel diverticulitis

Explanation: The imaging features are most consistent with acute, uncomplicated diverticulitis of the sigmoid colon. There is no evidence of abscess, fistula, or free perforation, which would indicate a complicated case.

4. Which of the following is a potential complication of this condition?

(1) Abscess

(2) Perforation

(3) Colovesical fistula

(4) All of the above

Explanation: Major complications of diverticulitis include abscess formation, perforation (either free or contained), and fistula development—most commonly colovesical fistulas. Abscesses occur in approximately 15% of acute diverticulitis cases, while fistulas develop in about 5%. Among patients requiring surgical intervention for diverticulitis, the incidence of fistula formation rises to as high as 20%.

5. Approximately 33% of patients with acute diverticulitis experience recurrence.

(1) True

(2) False

Explanation: Recurrence rates of diverticulitis range between 20% and 50%, with many sources estimating recurrence in approximately one-third of patients following an initial episode.

Findings and Diagnosis

Findings:

CT scan: Diverticula are seen in the proximal sigmoid colon, demonstrating mild mural thickening and adjacent fat stranding along the anterior aspect. An inflamed diverticulum with localized contrast enhancement is noted, consistent with acute diverticulitis with localized microperforation.

Multiple small gas foci arranged in a linear pattern were observed within the adjacent mesentery, surrounded by inflammatory changes, suggestive of microperforation without abscess formation. A portion of the distal ileum appeared mildly dilated, likely representing reactive localized ileus rather than true small bowel obstruction.

Differential Diagnosis

-

Uncomplicated sigmoid diverticulitis with microperforation

-

Sigmoid diverticulitis complicated by intramural abscess

-

Colorectal carcinoma

-

Epiploic appendagitis

-

Ischemic colitis

-

Pseudomembranous colitis

-

Ulcerative colitis

Diagnosis

Acute sigmoid diverticulitis with localized microperforation (Uncomplicated)

Discussion

Acute Sigmoid Diverticulitis with Localized Microperforation

Pathophysiology

An increase in intraluminal pressure—typically resulting from erosion of the diverticular wall by impacted food particles—initiates localized inflammation and mucosal necrosis, which can progress to either microperforation or macroperforation. These perforations are often contained by the surrounding pericolic fat or mesentery, thereby limiting the extent of inflammatory spread.

Major complications include:

-

Fistula formation

-

Abscess

-

Pneumoperitoneum

-

Bowel obstruction

-

Lower gastrointestinal bleeding

-

Portal venous pylephlebitis

Epidemiology

-

Acute diverticulitis is the third most common cause of gastrointestinal-related hospitalizations and a leading indication for elective colon resection.

-

Approximately 20% of adults under 40 have diverticulosis; prevalence rises to 60% by age 60.

-

In Western populations, 95% of diverticulosis involves the sigmoid colon; in contrast, right-sided involvement is more common in Asian populations.

-

Diverticulitis develops in 10–25% of patients with diverticulosis.

-

It occurs more frequently in males under 50 and females between 50 and 70, with a significantly higher incidence in females over 70.

-

Recurrence occurs in 20–50% of patients following an initial episode.

Clinical Presentation

-

Left lower quadrant abdominal pain

-

Nausea and vomiting

-

Fever and chills

-

Altered bowel habits

-

Occult blood in stool

-

In cases of free perforation and peritonitis, hypotension and shock

Imaging Features

CT Findings:

-

Focal colonic wall thickening with contrast enhancement

-

Pericolic stranding and mesenteric edema

-

Extraluminal microperforation into the surrounding fat

-

Pneumoperitoneum (if perforation is uncontained)

-

Abscess formation (in ~15% of acute diverticulitis cases)

-

Fistula formation (seen in ~5% of cases, and in 20% of those undergoing surgery)

Treatment

Medical management includes:

-

Bowel rest

-

Intravenous fluids

-

IV antibiotics

-

Analgesia

Additional interventions:

-

Percutaneous drainage for abscesses >4 cm

-

Emergency surgery may be required for:

-

Generalized peritonitis

-

Pneumoperitoneum

-

Clinical signs of peritoneal irritation

-

-

Elective surgery may be considered after:

-

Failed medical therapy

-

Fistula formation

-

Recurrent diverticulitis (≥2 episodes)

-

After resolution of the acute episode, a follow-up colonoscopy is recommended to rule out underlying colorectal carcinoma.

References

- Strate LL, Morris AM. Epidemiology, pathophysiology, and treatment of diverticulitis. Gastroenterology. 2019 Mar;156(5):1282-1298.e1. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2018.12.033.

- Tursi A, Papa A, Danese S. Review article: the pathophysiology and medical management of diverticulitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015 Apr;41(9):839–846. doi:10.1111/apt.13145.

- Hall JF, Roberts PL, Ricciardi R, Read TE, Marcello PW, Schoetz DJ. Long-term follow-up after an initial episode of diverticulitis: what are the predictors of recurrence? Dis Colon Rectum. 2011 Oct;54(10):1183–1189. doi:10.1097/DCR.0b013e318227f46f.

- Ambrosetti P, Becker C, Terrier F. Colonic diverticulitis: impact of imaging on surgical management—a prospective study of 542 patients. Eur Radiol. 2002 Feb;12(1):114–119. doi:10.1007/s003300100873.

- Meyer J, Krueger A, Habrich C, Reibetanz J, Germer CT, Riedl O. Current treatment options and the role of surgery for diverticular disease. Viszeralmedizin. 2015 Apr;31(2):112–118. doi:10.1159/000430430.

Comments

Post a Comment