Case Study: 62-Year-Old Woman with Abnormal Movement of the Left Arm, Nonketotic Hyperglycemic Hemichorea (NH-HC)

Nonketotic Hyperglycemic Hemichorea

1. Cause

Nonketotic hyperglycemic

hemichorea is caused by severe hyperglycemia without significant ketosis.

The condition predominantly affects elderly individuals with type 2 diabetes

mellitus and is characterized by unilateral chorea or hemiballismus,

which are involuntary, rapid, and irregular movements on one side of the body.

2. Etiology

- Underlying disease: Long-standing or newly

diagnosed type 2 diabetes mellitus.

- Precipitating factor: Extreme hyperglycemia

(often >300 mg/dL) without ketosis or acidosis.

- Metabolic dysfunction: Thought to cause energy

depletion in the basal ganglia, particularly the striatum (caudate

and putamen).

- Demographic predisposition: Most common in elderly

women of Asian descent, but can occur in any population.

3. Pathophysiology

The precise mechanism is not

fully understood, but several hypotheses have been proposed:

- Metabolic insult to the basal ganglia:

- Hyperglycemia leads to cellular dehydration

and altered neuronal metabolism.

- GABA and acetylcholine depletion due to impaired Krebs

cycle activity; GABA is crucial in inhibiting involuntary movements.

- Vascular compromise:

- Chronic hyperglycemia leads to microvascular

ischemia and disruption of the blood-brain barrier, particularly in

the basal ganglia.

- Hyperviscosity and perfusion deficits:

- Elevated serum glucose increases blood viscosity,

potentially leading to regional ischemia.

- Reactive astrocytosis:

- Seen on histology, suggesting a chronic degenerative

process.

- No significant ketone production:

- Distinguishes it from diabetic ketoacidosis-related

encephalopathy.

4. Epidemiology

- Prevalence: Rare; exact incidence

is unknown.

- Age: Typically affects elderly individuals (mean

age ~70).

- Gender: More common in females.

- Ethnicity: Higher incidence in Asian

populations (e.g., Korean, Japanese, Chinese).

- Type of diabetes: Almost exclusively seen

in type 2 diabetes mellitus.

- Laterality: Typically unilateral,

involving the side contralateral to the affected basal ganglia.

5. Clinical Presentation

- Primary symptom: Hemichorea or

hemiballismus (involuntary, irregular, often violent movements).

- It can involve limbs, face, and trunk.

- Movements are continuous, non-rhythmic, and disappear

during sleep.

- Mental status: Usually preserved;

patients are often alert.

- Other neurological signs: Rare, though mild focal

deficits may be observed.

- Duration: Symptoms may develop

over hours to days.

6. Imaging Features

CT Scan:

- Hyperdensity in the contralateral basal ganglia (usually the putamen).

- No mass effect or hemorrhage.

- Often misinterpreted as hemorrhage, but blood work

and clinical history help differentiate.

MRI (preferred modality):

- T1-weighted images: Hyperintensity in the contralateral

putamen and/or caudate nucleus.

- T2-weighted/FLAIR: Often normal or mildly

hypointense.

- DWI/ADC: Usually no diffusion restriction, helping

distinguish from acute infarct.

Key radiologic term: “Diabetic striatopathy”

refers to the imaging hallmark of striatal hyperintensity in nonketotic

hyperglycemia.

7. Treatment

A. Glycemic control:

- Primary and most effective intervention.

- Use insulin or oral hypoglycemic agents to

reduce blood glucose.

- Avoid rapid correction to prevent osmotic shifts.

B. Symptomatic treatment for

chorea:

- If involuntary movements are severe or persistent:

- Dopamine receptor blockers: e.g., haloperidol,

risperidone.

- Tetrabenazine: a vesicular monoamine

transporter inhibitor.

- Clonazepam or valproic acid: occasionally used.

C. Supportive care:

- Physical safety during involuntary movements.

- Monitoring for recurrent hyperglycemia.

8. Prognosis

- Generally favorable with prompt glucose

control.

- Symptom resolution:

- Most cases resolve within days to weeks

after correction of hyperglycemia.

- Some patients may have persistent or relapsing

symptoms.

- Reversibility of imaging findings:

- T1 hyperintensity may persist for months even after

clinical resolution.

- Recurrence:

- Rare but possible if glycemic control is not

maintained.

- Residual chorea:

- In a minority of patients, especially if diagnosis

and treatment are delayed.

Summary Table:

|

Aspect |

Key Details |

|

Cause |

Severe nonketotic

hyperglycemia |

|

Etiology |

Type 2 DM, poorly controlled

glucose |

|

Pathophysiology |

GABA depletion,

astrocytosis, striatal ischemia |

|

Epidemiology |

Elderly females, Asian

ethnicity |

|

Clinical Presentation |

Unilateral chorea/ballismus,

no altered mental status |

|

Imaging |

T1 hyperintensity in

contralateral striatum (MRI), CT hyperdensity |

|

Treatment |

Glycemic control, antichorea

meds if needed |

|

Prognosis |

Good with treatment, most

resolve fully |

=============================

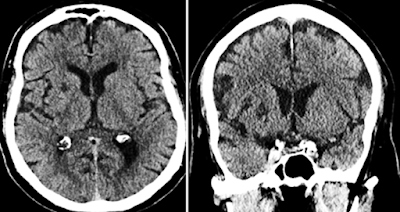

Case Study: 62-Year-Old Woman with Abnormal Movement of the Left Arm

Nonketotic Hyperglycemic Hemichorea

History and Imaging

-

A 62-year-old woman presented with abnormal involuntary movements of her left arm, which began one week prior.

-

Below are non-contrast axial and coronal CT images of the brain.

Quiz 1:

1. Where is the most prominent abnormality located?

(1) Left basal ganglia

(2) Right basal ganglia

(3) Left internal capsule

(4) Right internal capsule

(5) Left thalamus

(6) Right thalamus

Explanation: A hypodense area is observed in the right basal ganglia on the CT scan, consistent with diabetic striatopathy secondary to nonketotic hyperglycemia.

2. This abnormality is associated with a significant mass effect.

(1) True

(2) False

Explanation: Although the lesion appears hypodense on CT, it is not associated with mass effect, midline shift, or surrounding edema. This helps differentiate it from conditions such as infarction or hemorrhage.

3. What is the most appropriate imaging modality for further evaluation?

(1) MRI

(2) CT angiography

(3) Plain radiograph

Explanation: MRI is the modality of choice to further characterize basal ganglia abnormalities. In nonketotic hyperglycemic hemichorea, T1-weighted images typically show hyperintensity in the striatum, which confirms the diagnosis.

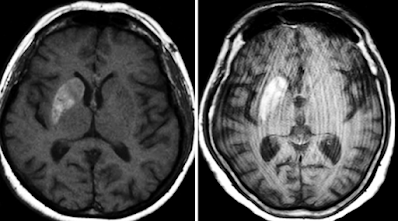

Additional Clinical History and MRI Imaging

-

The patient has a history of poorly controlled chronic diabetes mellitus.

-

Brain MRI was subsequently performed for further evaluation.

Quiz 2:

1. Is there abnormal contrast enhancement?

(1) True

(2) False

Explanation: No abnormal contrast enhancement is seen. In nonketotic hyperglycemic hemichorea, contrast enhancement is typically absent on MRI.

2. Is diffusion restricted?

(1) True

(2) False

Explanation: Diffusion-weighted imaging does not show restriction, helping distinguish this entity from acute ischemic stroke.

3. Is there hemorrhage?

(1) True

(2) False

Explanation: Despite high signal intensity in the basal ganglia on T1-weighted images or hyperdensity on CT, there is no evidence of true hemorrhage or associated mass effect.

4. What is the most likely diagnosis?

(1) Wilson’s disease

(2) Hypertensive hemorrhage

(3) Benign calcification

(4) Carbon monoxide poisoning

(5) Manganese deposition in hepatic encephalopathy

(6) Nonketotic hyperglycemic hemichorea

Explanation: The clinical presentation, history of poorly controlled type 2 diabetes, and characteristic imaging findings (T1 hyperintensity in the contralateral basal ganglia without enhancement or diffusion restriction) support this diagnosis.

Findings and Diagnosis

CT Findings

-

Often normal, but may show hyperdensity in the basal ganglia.

MRI Findings

-

T1-weighted images: High signal intensity in the basal ganglia, especially the caudate nucleus and putamen (with or without globus pallidus involvement).

-

T2/FLAIR: Often normal or only mildly hyperintense—less sensitive.

-

No contrast enhancement or restricted diffusion.

-

Susceptibility imaging (SWI/GRE): Usually normal in early stages; may show low signal intensity later due to metal deposition (e.g., manganese or iron).

Differential Diagnosis

-

Wilson’s disease

-

Hypertensive hemorrhage

-

Benign calcification

-

Carbon monoxide poisoning

-

Manganese deposition in hepatic encephalopathy

-

Nonketotic hyperglycemic hemichorea (most consistent)

Diagnosis

-

Nonketotic Hyperglycemic Hemichorea (NKH-HC)

Discussion

Pathophysiology

In NKH-HC, hyperviscosity from severe hyperglycemia can reduce cerebral perfusion. This may lead to anaerobic metabolism and depletion of GABA, a key inhibitory neurotransmitter in the thalamocortical circuit, resulting in involuntary movements (chorea/ballismus). Although the exact histopathologic mechanism is unclear, transient ischemia and reactive astrocytosis may lead to manganese accumulation, which shortens T1 relaxation and causes the T1 hyperintensity observed on MRI.

Epidemiology

-

Typically occurs in elderly patients with poorly controlled type 2 diabetes.

-

The estimated prevalence is less than 1 per 100,000 people.

-

Mean age: 71 years.

-

Female-to-male ratio: 2:1.

-

Higher incidence reported in Asian populations.

Clinical Presentation

-

Acute-onset, unilateral involuntary hyperkinetic movements (chorea or ballismus).

-

Movements are sudden, jerky, and purposeless, sometimes violent and flinging.

-

Blood tests typically show marked hyperglycemia (≥400 mg/dL) with negative ketones and elevated HbA1c (>12%).

-

Symptoms generally improve with normalization of blood glucose.

Imaging Summary

-

Side: Contralateral to the clinical symptoms.

-

CT: May show hyperdensity in the basal ganglia, often interpreted initially as hemorrhage.

-

MRI:

-

T1 hyperintensity in the caudate and putamen is characteristic.

-

T2/FLAIR changes are subtle.

-

No enhancement or diffusion restriction.

-

SWI/GRE: Normal early; may show low signal later due to mineral deposition.

-

Treatment

-

Primary therapy: Tight glycemic control.

-

Symptoms often resolve within days to weeks.

-

If chorea persists, dopamine receptor blockers such as haloperidol may be used.

- Oh, S. H., Lee, K. Y., Im, J. H., & Lee, M. S. (2002). Chorea associated with non-ketotic hyperglycemia and hyperintensity basal ganglia lesion on T1-weighted brain MRI study: A meta-analysis of 53 cases, including four present cases. Journal of Neurological Sciences, 200(1–2), 57–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-510X(02)00131-4

- Lai, P. H., Tien, R. D., Chang, M. H., Yang, C. F., Pan, H. B., & Chang, F. M. (1996). Chorea-ballismus with nonketotic hyperglycemia in primary diabetes mellitus. AJNR. American Journal of Neuroradiology, 17(6), 1057–1064. [PubMed ID: 8791900]

- Chang, K. H., Tsou, J. C., Chen, S. T., Ro, L. S., & Lee, T. H. (1996). MRI of striatal lesions in patients with chorea and non-ketotic hyperglycemia: T1-weighted MRI hyperintensity correlates with serum glucose levels. Neuroradiology, 38(6), 516–520. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00588287

- Wang, H. C., & Hsu, J. L. (1999). Hyperglycemia-induced unilateral basal ganglion lesions with and without hemichorea: A PET study. Journal of Neurology, 246(9), 775–779. https://doi.org/10.1007/s004150050466

- Ohara, S., Nakagawa, S., Tabata, K., Hashimoto, T., & Naritomi, H. (2001). Hemichorea-hemiballism associated with hyperglycemia: A clinical and Neuroradiologic study. Journal of Neurology, 248(11), 1069–1073. https://doi.org/10.1007/s004150170033

Comments

Post a Comment