Acute pontine hemorrhage

1. Introduction

Acute pontine hemorrhage is a catastrophic subtype of intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH), characterized by bleeding within the pons of the brainstem. It accounts for a significant proportion of brainstem hemorrhages and is associated with high mortality and morbidity due to the anatomical concentration of critical autonomic, motor, and sensory pathways.

2. Etiology and Causes

The primary and secondary causes of pontine hemorrhage can be grouped into several categories:

A. Primary (Spontaneous) Hemorrhage

-

Hypertension (the most common cause)

Chronic uncontrolled hypertension leads to lipohyalinosis and fibrinoid necrosis of small perforating arteries, especially the paramedian branches of the basilar artery.

B. Secondary (Structural or Systemic Conditions)

-

Vascular Malformations

-

Cavernous malformations (cavernomas)

-

Arteriovenous malformations (AVMs)

-

-

Hemorrhagic conversion of ischemic stroke

-

Coagulopathies

-

Anticoagulation (warfarin, DOACs)

-

Platelet disorders

-

Liver failure

-

-

Neoplasms

-

Gliomas, metastases (e.g., melanoma, renal cell carcinoma)

-

-

Trauma

-

Diffuse axonal injury can lead to pontine hemorrhages.

-

-

Drug-related

-

Amphetamines, cocaine (vasculopathy)

-

-

Systemic vasculitis

-

Primary CNS vasculitis, lupus, polyarteritis nodosa

-

-

Amyloid angiopathy

-

Rare in the brainstem, more common in lobar locations

-

3. Pathophysiology

A. Vascular Disruption

-

The pons is supplied by perforating arteries from the basilar artery.

-

Chronic hypertension leads to weakening of vessel walls → Charcot-Bouchard aneurysms → rupture → hemorrhage.

B. Space-occupying Hemorrhage

-

Hemorrhage exerts mass effect in a confined region, leading to:

-

Compression of the reticular activating system (RAS) → impaired consciousness.

-

Disruption of cranial nerve nuclei, long tracts (corticospinal, spinothalamic), and autonomic centers.

-

C. Secondary Injury

-

Perihematomal edema

-

Inflammatory response

-

Neurotoxicity from blood breakdown products (iron, hemoglobin, thrombin)

4. Epidemiology

-

Incidence: Pontine hemorrhage represents 5-10% of all spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhages.

-

Age: Most common in middle-aged to elderly adults (50–70 years)

-

Sex: Slight male predominance.

-

Geography: More prevalent in East Asian populations (possibly due to higher rates of hypertension and cerebral small vessel disease).

-

Mortality: Up to 60-70% within the first 48 hours, especially with coma at onset and large hematomas.

-

Risk Factors:

-

Chronic hypertension

-

Smoking

-

Excessive alcohol consumption

-

Poor compliance with antihypertensive therapy

-

Use of antithrombotic agents

-

5. Clinical Symptoms

Symptoms depend on the size, location, and expansion of the hemorrhage. Pontine hemorrhage causes rapid neurologic deterioration due to the high density of critical structures.

A. Classic Presentation

-

Acute coma or rapidly decreasing consciousness

-

Quadriplegia: Bilateral corticospinal tract involvement

-

Pinpoint pupils: Disruption of sympathetic descending fibers; reactive or non-reactive

-

Gaze palsies: Disruption of horizontal gaze centers (PPRF, abducens nucleus)

-

Facial weakness: Bilateral facial palsy is possible

-

Respiratory dysfunction:

-

Apneustic or ataxic breathing

-

Central respiratory failure in large bleeds

-

-

Decerebrate posturing or flaccidity

B. Minor/Small Hemorrhages

-

Diplopia, dysarthria, ataxia

-

Vertigo

-

Facial numbness or weakness

-

Hemiparesis (if unilateral)

6. Imaging Findings

A. Non-contrast CT (first-line)

-

Hyperdense lesion in the pons, usually in a central or paramedian location

-

"Bilateral teardrop" or "butterfly" sign in extensive bleeds

-

Mass effect: Compression of the fourth ventricle, hydrocephalus

-

Ventricular extension may be present

B. MRI Brain

T1/T2/FLAIR: Hyperacute hemorrhage may appear isointense or hypointense.

-

Gradient Echo / SWI: Sensitive to blood products, useful in chronic microbleeds or cavernomas.

-

Diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI): Can identify concurrent ischemic injury.

-

MR Angiography / Venography: To rule out vascular malformations

C. CT Angiography

Helps evaluate for AVMs or aneurysms

-

Spot sign: Contrast extravasation may indicate active bleeding

D. Digital Subtraction Angiography (DSA)

Gold standard for vascular lesion detection, but rarely needed in typical hypertensive hemorrhage.

7. Treatment

A. Acute Management

1. Airway and Cardiopulmonary Stabilization

-

Intubation is often required in cases of coma or respiratory compromise

2. Blood Pressure Management

-

Rapid lowering to SBP <140 mmHg (per AHA/ASA guidelines)

-

Agents: Nicardipine, labetalol, clevidipine

3. Intracranial Pressure (ICP) Control

-

Head elevation to 30°

-

Osmotic agents (mannitol, hypertonic saline)

-

Consider CSF diversion (EVD) if hydrocephalus is present

4. Hemostatic Therapy

-

Reversal of anticoagulation:

-

Vitamin K, PCC for warfarin

-

Idarucizumab (for dabigatran), andexanet alfa (for apixaban/rivaroxaban)

-

-

Platelet transfusion (controversial)

5. Seizure Prophylaxis

-

Not routinely recommended unless a clinical seizure occurs

B. Surgical Intervention

-

Controversial due to deep location and high surgical risk

-

Stereotactic aspiration or endoscopic evacuation may be considered in select patients with a large hematoma and deteriorating consciousness

-

Ventriculostomy for hydrocephalus

C. Supportive Care

-

ICU monitoring

-

Nutrition, DVT prophylaxis, prevention of complications (pneumonia, UTI)

D. Rehabilitation

-

Early and aggressive rehabilitation for survivors

-

Multidisciplinary approach: Physical, occupational, and speech therapy

8. Prognosis

A. Determinants of Outcome

-

Initial Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score

-

Hematoma volume

-

Extension into the fourth ventricle

-

Presence of hydrocephalus

-

Age

-

Comorbidities

B. Prognostic Scales

-

ICH score: Often adapted for pontine hemorrhages

-

Volume >5 mL and GCS ≤8 associated with poor prognosis

C. Mortality

-

Overall in-hospital mortality: 30–60%

-

Brainstem hemorrhages >10 mm in diameter: very poor outcome

-

Patients with small hemorrhages (<3 mL) may recover with minimal deficit

D. Functional Outcome

-

Survivors are often left with:

-

Cranial nerve deficits

-

Motor weakness or quadriplegia

-

Ataxia

-

Dysarthria or dysphagia

-

-

Some make a near-complete recovery if the bleed is small and rapidly treated

9. Differential Diagnosis

-

Pontine infarction (especially paramedian infarcts)

-

Tumors with hemorrhagic component (glioma, metastasis)

-

Demyelinating diseases

-

Central pontine myelolysis (non-hemorrhagic)

-

Encephalitis (e.g., Listeria rhombencephalitis)

10. Prevention

Primary

-

Control of hypertension (most critical)

-

Smoking and alcohol cessation

-

Screening for vascular malformations in at-risk patients

Secondary

-

Adequate control of BP post-stroke

-

Cautious use of anticoagulation in high-risk patients

Case study: Acute Pontine Hemorrhage in a 50-Year-Old Woman with Hypertension

Acute Pontine Hemorrhage

History and Imaging

-

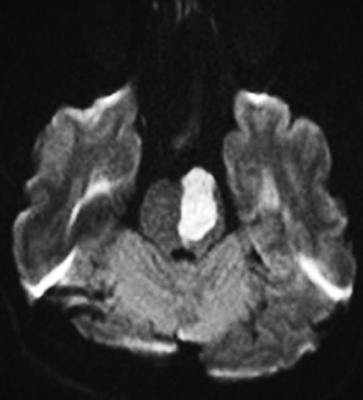

A 50-year-old woman with a known history of hypertension presented with an acute pontine hemorrhage, as demonstrated on computed tomography (arrow).

As a result, she developed quadriplegia.

-

At 30-month follow-up, she reported experiencing difficulty reading due to oscillopsia.

-

Physical examination revealed pendular nystagmus characterized primarily by vertical eye movements, with minor horizontal and torsional components, occurring at a frequency of approximately 2 cycles per second.

-

She also exhibited palatal myoclonus, consisting of rhythmic, involuntary contractions of the soft palate and palatopharyngeal arch at a rate of 1 to 2 cycles per second.

-

T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain demonstrated hyperintensity and hypertrophy of the inferior olivary nuclei.

Quiz:

What clinical manifestation is expected in this patient?

(1) Asymmetrical mydriasis

(2) Ataxic hemiparesis

(3) Hypothermia

(4) Quadriplegia

(5) Upward gaze palsy

Correct Answer: (4) Quadriplegia

Explanation:

The patient described in this case developed quadriplegia following an acute pontine hemorrhage, which is consistent with the known clinical sequelae of damage to the bilateral corticospinal tracts within the ventral pons. The corticospinal tracts descend through the basis pontis and are responsible for voluntary motor control of the limbs. A hemorrhage that affects both sides of the pons can disrupt these pathways, leading to complete paralysis of all four limbs. In addition to motor impairment, pontine hemorrhages may also affect cranial nerve nuclei and adjacent reticular structures, potentially resulting in coma, abnormal eye movements, and autonomic instability, depending on the extent and location of the bleed. However, in this specific case, the hallmark feature following the hemorrhage was quadriplegia, as explicitly stated in the clinical history.

Discussion

Acute Pontine Hemorrhage

Acute pontine hemorrhage refers to bleeding within the pons, a part of the brainstem located in the lower portion of the brain. The brainstem is responsible for numerous vital functions, including the regulation of respiration, heart rate, and consciousness. Hemorrhage in this region can lead to severe neurological deficits and potentially life-threatening complications.

Key aspects of acute pontine hemorrhage include:

Etiology:

Acute pontine hemorrhage most commonly results from the rupture of small penetrating arteries within the pons. The most frequent underlying cause is chronic hypertension, which leads to lipohyalinosis and microaneurysm formation in the brainstem vasculature. Other potential causes include arteriovenous malformations (AVMs), cerebral aneurysms, vascular tumors, and head trauma. Among these, chronic hypertension is considered the most significant risk factor.

Clinical Presentation:

Symptoms vary depending on the size and precise location of the hemorrhage, but typically include the sudden onset of neurological deficits such as weakness or paralysis (often unilateral), dysarthria, dysphagia, altered level of consciousness, coma, and respiratory irregularities. In large hemorrhages, quadriplegia may result from involvement of the corticospinal tracts, and disruption of the reticular activating system can lead to coma.

Diagnosis:

The diagnosis is primarily based on clinical presentation and neuroimaging. Non-contrast computed tomography (CT) of the brain is the imaging modality of choice in the acute setting and is highly sensitive for detecting hemorrhage. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), particularly T2-weighted and susceptibility-weighted sequences, may provide additional information regarding hemorrhage evolution and secondary brainstem involvement.

Management:

Treatment of acute pontine hemorrhage focuses on stabilizing the patient and managing complications. Key aspects include blood pressure control, reduction of intracranial pressure (ICP), and supportive measures such as mechanical ventilation when respiratory function is compromised. In rare cases where the hemorrhage exerts a significant mass effect or hydrocephalus, surgical intervention such as ventricular drainage may be considered, although surgical options are limited due to the anatomical complexity and critical functions of the brainstem.

Prognosis:

The prognosis of acute pontine hemorrhage depends on several factors, including hemorrhage size and location, extent of neurological impairment, and the timeliness of medical intervention. Large pontine hemorrhages, particularly those involving the midline or bilateral structures, are associated with high morbidity and mortality. Functional recovery is often limited, and persistent neurological deficits are common.

Rehabilitation:

Following the acute phase, comprehensive rehabilitation is essential to optimize functional recovery and adapt to residual neurological impairments. This may involve physical therapy, occupational therapy, speech and swallowing therapy, and psychosocial support. The goals of rehabilitation include improving mobility, communication, independence in daily activities, and overall quality of life.

In summary, acute pontine hemorrhage is a critical medical emergency that requires prompt recognition and multidisciplinary management. Optimal outcomes depend on early intervention, intensive supportive care, and long-term rehabilitation. Neurologists, neurosurgeons, intensivists, and rehabilitation specialists play vital roles in the continuum of care for affected patients.

Reference

- Wijdicks EFM. The Clinical Practice of Critical Care Neurology. Oxford University Press; 2016.

- Caplan LR. Caplan’s Stroke: A Clinical Approach. 5th ed. Cambridge University Press; 2016.

- Schmahmann JD, Ko R. "Acute Pontine Hemorrhage: Clinical Features and Prognostic Indicators." Neurology. 1992;42(1):170–175. doi: 10.1212/WNL.42.1.170

- Kase CS, Norrving B, Levine SR, et al. "Pontine hemorrhage: clinical features, CT findings and prognosis." Stroke. 1994;25(3):484–491. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.25.3.484

- Adams RD, Victor M, Ropper AH. Principles of Neurology. 11th ed. McGraw-Hill Education; 2019.

Comments

Post a Comment