Interstitial lung disease and Sjögren's syndrome

1. Cause and Etiology

Sjögren’s Syndrome (SS) is a

chronic autoimmune disease characterized primarily by lymphocytic infiltration

of exocrine glands, leading to dry eyes and dry mouth. However, it is also a systemic disorder and can involve multiple

organs, including the lungs,

resulting in interstitial lung disease

(ILD).

ILD in Sjögren’s syndrome is considered secondary to the autoimmune process. The exact cause remains unknown, but the key

factors include:

·

Autoimmunity:

Production of autoantibodies (anti-Ro/SSA and anti-La/SSB).

·

Genetic predisposition:

Certain HLA alleles are associated with SS (e.g., HLA-DR, HLA-DQ).

·

Environmental triggers:

Viral infections (e.g., Epstein-Barr virus, cytomegalovirus), and dust or

chemical exposure may contribute.

·

Chronic inflammation:

Persistent lymphocytic infiltration and cytokine production contribute to

fibrosis and lung damage.

2.

Pathophysiology

ILD in Sjögren’s Syndrome arises due to immune-mediated injury to the lung

parenchyma:

·

Initial immune response

involves lymphocytic infiltration (primarily CD4+ T cells) around bronchioles and alveoli.

·

Progressive alveolar epithelial cell injury and endothelial damage occur.

·

This leads to fibroblast activation, collagen deposition, and pulmonary fibrosis in advanced stages.

·

The disease can affect:

o

Small airways:

resulting in bronchiolitis.

o

Interstitium: causing

interstitial pneumonitis and fibrosis.

o

Alveolar epithelium:

contributing to impaired gas exchange.

The most common histopathologic patterns

of ILD in Sjögren’s include:

·

Nonspecific interstitial pneumonia (NSIP) –

most common.

·

Lymphocytic interstitial pneumonia (LIP) –

seen in some cases.

·

Usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP) –

less common but has a worse prognosis.

·

Organizing pneumonia (OP) –

may also be observed.

3.

Epidemiology

·

Prevalence of ILD in Sjögren’s syndrome:

ranges from 9% to 20% in

clinically diagnosed patients, but subclinical involvement may be more frequent

(up to 75% on high-resolution CT).

·

More common in:

o

Women (Sjögren’s

female: male ratio is ~9:1)

o

Middle-aged individuals,

typically diagnosed betweenthe ages of 40–60.

·

ILD is more frequent in primary Sjögren’s syndrome than in secondary (associated with RA or SLE).

Risk factors for ILD in SS:

·

Male sex

·

Older age

·

Presence of anti-Ro/SSA and/or

anti-La/SSB antibodies

·

Longer disease duration

·

Low complement levels (C3, C4)

·

Cryoglobulinemia

4.

Clinical Presentation

Symptoms may be subtle or nonspecific in early disease, and ILD may be

diagnosed incidentally. Common features include:

·

Dry cough (chronic and

non-productive)

·

Progressive exertional dyspnea

·

Fatigue

·

Chest tightness or discomfort

·

Clubbing and cyanosis (in

advanced disease)

·

Fine basilar crackles on

auscultation

·

Some patients have extrapulmonary symptoms of SS: dry eyes,

dry mouth, parotid gland swelling, and arthralgias.

5.

Imaging Features

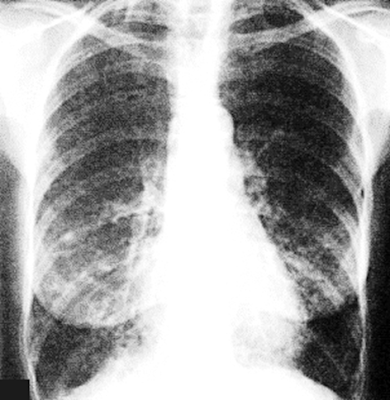

Chest X-ray

·

May be normal in early stages.

·

Later stages show reticulonodular patterns, volume loss,

and interstitial markings,

especially in the lower lobes.

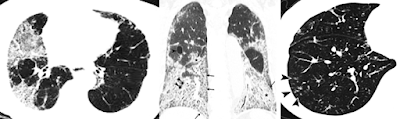

High-Resolution CT (HRCT) – Gold Standard

Common

patterns in SS-ILD:

·

NSIP pattern:

o

Ground-glass opacities

o

Subpleural sparing

o

Reticular abnormalities

·

LIP pattern:

o

Diffuse ground-glass attenuation

o

Thin-walled cysts

o

Centrilobular nodules

·

UIP pattern (in

fewer cases):

o

Honeycombing

o

Traction bronchiectasis

o

Subpleural and basal predominance

·

Bronchiolitis features:

tree-in-bud nodules, air trapping on expiratory scans.

Pulmonary Function Tests (PFTs)

·

Restrictive

pattern: ↓ FVC, ↓ TLC, ↓ DLCO

·

Obstructive changes if

small airways are involved (e.g., follicular bronchiolitis)

6.

Treatment

Management of SS-ILD depends on

severity, pattern of lung involvement, and presence of progressive disease.

Pharmacologic treatment

·

Glucocorticoids:

o

First-line for symptomatic or

progressive ILD.

o

Prednisone 0.5–1 mg/kg/day, tapered over

months.

·

Immunosuppressive agents:

o

Azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil, or cyclophosphamide are used for

steroid-sparing or non-responsive cases.

·

Rituximab (anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody):

o

Shown efficacy in LIP and NSIP;

especially useful in patients with B-cell hyperactivity.

·

Nintedanib or pirfenidone:

o

Considered for progressive fibrosing ILD

regardless of etiology (anti-fibrotic agents).

·

Antibiotics:

o

For recurrent infections or

bronchiectasis.

·

Supportive care:

o

Oxygen therapy

o

Pulmonary rehabilitation

o

Smoking cessation

o

Vaccinations (influenza, pneumococcal)

7.

Prognosis

·

Prognosis varies depending on the histologic subtype, degree of fibrosis,

and response to therapy.

·

NSIP and LIP have

a better prognosis than UIP.

·

UIP pattern is associated with poor outcomes, with a median survival of

~3–5 years if progressive.

·

Some patients remain stable for years, while others develop progressive fibrosing ILD.

·

Risk of lymphoma (especially MALT lymphoma) is increased in SS

and may mimic or coexist with LIP.

·

Mortality in SS-ILD is

higher than in SS without lung involvement, often due to respiratory failure or infections.

Summary Table

|

Feature |

Details |

|

Cause |

Autoimmune

destruction in Sjögren’s syndrome |

|

Pathophysiology |

Lymphocytic

infiltration → inflammation → fibrosis |

|

Epidemiology |

9–20% of SS patients

(clinical), up to 75% (radiographic); F > M |

|

Clinical Presentation |

Dry cough, dyspnea,

fatigue, and crackles |

|

Imaging Features |

HRCT: NSIP, LIP, or

UIP patterns; cysts in LIP |

|

Treatment |

Steroids,

immunosuppressants, rituximab, antifibrotics |

|

Prognosis |

NSIP/LIP better than

UIP; progression varies; ↑ lymphoma risk |

===============================

Case Study: A 68-Year-Old Woman Presenting with Dyspnea

Interstitial Lung Disease and Sjögren’s Syndrome

History and Imaging

-

A 68-year-old woman with a known history of Sjögren’s syndrome presented with complaints of dyspnea.

Quiz

1. Which of the following should be included in the differential diagnosis of a patient presenting with dyspnea?

(1) Pulmonary embolism

(2) Pneumothorax

(3) Myocardial infarction

(4) Pneumonia

(5) Pleural effusion

(6) All of the above

Explanation: All of the listed conditions are important and potentially life-threatening causes of dyspnea. A comprehensive differential diagnosis should consider all of these possibilities when evaluating a patient with shortness of breath.

2. The most specific autoantibody associated with Sjögren’s syndrome is the anti-Yo antibody.

(1) True

(2) False

Explanation: The anti-Yo antibody is typically associated with paraneoplastic cerebellar degeneration, not Sjögren’s syndrome. The most characteristic autoantibodies in Sjögren’s syndrome are anti-SSA/Ro and anti-SSB/La antibodies, which are present in the majority of affected patients.

3. A patient with honeycombing on imaging typically shows thick-walled, stacked cystic airspaces involving the subpleural region.

(1) True

(2) False

Explanation: Honeycombing refers to clustered cystic airspaces ranging from 3 to 10 mm in diameter, usually located in the subpleural region. These cysts are stacked in multiple layers, have well-defined walls, and are a hallmark of end-stage fibrotic interstitial lung disease.

Findings and Diagnosis

Findings:

Bilateral basilar traction bronchiectasis and honeycombing are consistent with interstitial lung disease, demonstrating a typical pattern of interstitial pneumonia.

Differential Diagnosis:

-

Interstitial pulmonary fibrosis

-

Asbestosis

-

Hypersensitivity pneumonitis

-

Sarcoidosis

-

Interstitial pneumonitis

Final Diagnosis:

Interstitial Lung Disease associated with Sjögren's Syndrome

Discussion

Interstitial Lung Disease and Sjögren’s Syndrome

Epidemiology and Pathophysiology:

Interstitial lung disease (ILD) encompasses a broad spectrum of pulmonary disorders characterized by varying degrees of inflammation and fibrosis of the lung interstitium. Known etiologies include connective tissue diseases, drug-induced injury, and environmental exposures. In cases where no definitive cause is identified, the condition is classified as idiopathic interstitial pneumonia (IIP). Among connective tissue diseases associated with ILD are rheumatoid arthritis, systemic sclerosis, polymyositis/dermatomyositis, Sjögren’s syndrome, systemic lupus erythematosus, and mixed connective tissue disease.

Sjögren’s syndrome is clinically characterized by the triad of xerophthalmia (dry eyes), xerostomia (dry mouth), and arthritis. It affects approximately 0.1% of the general population and up to 3% of the elderly. Thoracic involvement is common, with lymphocytic interstitial pneumonia (LIP) being the most frequent pulmonary manifestation. Other airway-related complications include follicular bronchiolitis, bronchiectasis, and small airway disease. Less common manifestations include interstitial pneumonia with fibrosis, lymphoma, pulmonary hypertension, and pleural effusions or pleural fibrosis.

Radiologic Findings:

The most common radiologic presentation is a reticulonodular pattern predominantly in the lower lobes, which may reflect underlying lymphocytic interstitial pneumonia or fibrosing interstitial lung disease. The presence of honeycombing and/or ground-glass opacities suggests established fibrosis. In advanced cases, traction bronchiectasis and architectural distortion may be observed.

Treatment:

Management of ILD associated with connective tissue disease, including Sjögren’s syndrome, may include:

-

Corticosteroids

-

Immunosuppressive agents (e.g., azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil)

-

Biologic agents (e.g., rituximab)

-

Oxygen therapy

-

Bronchodilators

Despite available treatments aimed at controlling inflammation and preventing progression, a definitive cure remains elusive, and the prognosis depends on the extent of fibrosis and response to therapy.

References

-

Flament, T., Bigot, A., Chaigne, B., Henique, H., Diot, E., & Marchand-Adam, S. (2016). Pulmonary manifestations of primary Sjögren’s syndrome. European Respiratory Review, 25(140), 110–123. https://doi.org/10.1183/16000617.0065-2015

-

Ito, I., Nagai, S., Kitaichi, M., Nicholson, A. G., Johkoh, T., Noma, S., ... & Izumi, T. (2005). Pulmonary manifestations of primary Sjögren’s syndrome: a clinical, radiologic, and pathologic study. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, 171(6), 632–638. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.200405-655OC

-

Enomoto, Y., Nakamura, Y., Colby, T. V., Johkoh, T., Sumikawa, H., Doi, T., ... & Suda, T. (2013). Radiologic-pathologic correlation of pleuroparenchymal fibroelastosis. European Respiratory Journal, 43(2), 447–457. https://doi.org/10.1183/09031936.00014013

-

Ramos-Casals, M., Brito-Zerón, P., Sisó-Almirall, A., Bosch, X. (2012). Primary Sjögren syndrome. BMJ, 344, e3821. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.e3821

-

Parambil, J. G., Myers, J. L., Lindell, R. M., Matteson, E. L., & Ryu, J. H. (2006). Interstitial lung disease in primary Sjögren syndrome. Chest, 130(5), 1489–1495. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.130.5.1489

Comments

Post a Comment