Pulmonary laceration

Definition

A pulmonary laceration is a traumatic injury to the lung parenchyma

characterized by tearing of the lung tissue, often accompanied by disruption of

the alveoli, bronchioles, and pulmonary vasculature. It frequently results in hemorrhage

and/or air leakage, forming hematomas or pneumatoceles.

Cause and Etiology

Pulmonary lacerations are caused by blunt or penetrating trauma to

the chest. They can also result from iatrogenic injuries or high-impact

acceleration-deceleration forces.

Common Causes:

- Blunt chest

trauma:

- Motor vehicle collisions

(MVCs)

- Falls from height

- Sports injuries

- Blast injuries

- Penetrating

trauma:

- Gunshot wounds

- Stab wounds

- Impalement

- Iatrogenic

trauma:

- Thoracic surgery (e.g.,

lobectomy, thoracotomy)

- Central venous

catheterization

- Chest tube insertion

- Barotrauma:

- Positive-pressure

ventilation

- Explosions causing

over-pressurization

Pathophysiology

The mechanism of lung laceration depends on the type and force of trauma:

- Blunt trauma compresses the chest wall, shearing the lung

against the ribs, spine, or mediastinum, leading to tears in the fragile

lung parenchyma.

- Penetrating

trauma directly disrupts lung

tissue and pulmonary vasculature.

- Rapid

deceleration (e.g., MVC)

may cause the lung to tear at its points of fixation (e.g., hilum).

Following the tear:

- Blood and/or

air enter the newly formed

cavity.

- If blood predominates, a pulmonary

hematoma forms.

- If air predominates,

especially when connected to bronchioles, a traumatic pneumatocele

may form.

- Surrounding alveoli

collapse, and inflammation may ensue.

- There is a risk of secondary

infection, especially with retained hematomas.

Epidemiology

- Most often seen in young

adults and males due to higher exposure to trauma (e.g., in MVCs or

assaults).

- Incidence is not well

reported independently, as pulmonary lacerations are usually found in

conjunction with pulmonary contusions and other thoracic injuries.

- Present in up to 5–10%

of blunt chest trauma cases, depending on the mechanism and severity.

Clinical Presentation

Pulmonary lacerations often occur with other thoracic injuries, so signs

may overlap with contusions, rib fractures, or hemothorax.

Symptoms:

- Chest pain

- Dyspnea or tachypnea

- Hemoptysis (coughing up

blood)

- Cough

- Respiratory distress in

severe cases

Signs:

- Decreased breath sounds

- Subcutaneous emphysema

(especially with associated pneumothorax)

- Signs of hypovolemia (if

bleeding is significant)

- Hypoxia or hypercapnia, depending on the extent

Imaging Features

Pulmonary lacerations may not be immediately visible on chest radiographs

and often require CT scanning for accurate detection.

1.

Chest X-Ray:

- It may appear normal early

on

- Later, it may show:

- Air-fluid levels

- Cavitary lesions (if

pneumatocele forms)

- Localized consolidation

or opacities

1.

CT Chest (Gold Standard):

- Better visualization of:

- Cystic or cavitary

lesions with or without air-fluid levels

- Associated injuries

(contusion, pneumothorax, hemothorax, rib fractures)

- Types of

pulmonary lacerations (per Wagner

classification):

- Type I: Shear injury near the spine in children/young

adults

- Type II: Peripheral laceration from rib fracture

- Type III: Rupture due to compression against the spine

- Type IV: Direct penetrating trauma

3. Follow-up Imaging:

- Monitoring for resolution

or complications (e.g., abscess formation)

Treatment

Supportive Care (Mainstay):

- Oxygen

supplementation

- Pain control (e.g., opioids, nerve blocks)

- Pulmonary

toilet and incentive

spirometry to prevent atelectasis

- Observation for small, asymptomatic lacerations

Drainage:

- Chest tube

insertion if:

- Significant pneumothorax

- Hemothorax

- Tension physiology

Surgical Intervention (Rare):

- Indicated in cases of:

- Persistent bleeding

- Large air leaks

- Non-resolving hematoma

or infection

- Failure of conservative

management

Antibiotics:

- Not routinely used unless

evidence of infection or during operative intervention

Prognosis

General Outlook:

- Good prognosis with

appropriate supportive care.

- Most pulmonary

lacerations heal spontaneously within 2–3 weeks.

Complications:

- Infection or

abscess

- Hemothorax or

pneumothorax

- Persistent

air leak

- Bronchopleural

fistula

- Scarring or

fibrosis

Prognostic Factors:

- Severity of trauma

- Presence of associated

injuries (e.g., contusion, rib fractures, head trauma)

- Timing and adequacy of

treatment

- Development of

complications (e.g., infected hematoma)

Summary Table

|

Aspect |

Details |

|

Cause |

Blunt or penetrating chest trauma |

|

Pathophysiology |

Tearing of lung tissue → air/blood leakage → pneumatocele/hematoma |

|

Epidemiology |

Common in young adult males after trauma (e.g., MVCs) |

|

Clinical Signs |

Chest pain, dyspnea, hemoptysis, hypoxia |

|

Imaging |

CT shows cavitary lesions; X-ray may show air-fluid levels |

|

Treatment |

Supportive care, chest tube if needed, and rarely surgery |

|

Prognosis |

Favorable; most heal within weeks unless complicated |

==========================================

Case study: Pulmonary Laceration in a 38-Year-Old Female Following a Motor Vehicle Rollover

Pulmonary Laceration

Clinical History and Imaging

-

A 38-year-old female with a medical history notable for scoliosis and chronic narcotic use presented to the emergency department following a motor vehicle rollover accident. The patient was reportedly ejected through the sunroof at the time of the collision.

-

A chest radiograph was obtained upon arrival for initial assessment.

Quiz 1:

What is the most significant finding on the chest radiograph?

(1) Rib fracture

(2) Airspace opacities

(3) Pneumothorax

(4) All of the above

Answer and Explanation:

Multiple airspace opacities are observed in the left lung, adjacent to areas of acute rib fractures, suggesting underlying pulmonary laceration or contusion. In addition, a small-to-moderate left-sided pneumothorax is identified, evidenced by the presence of a white visceral pleural line at the apex.

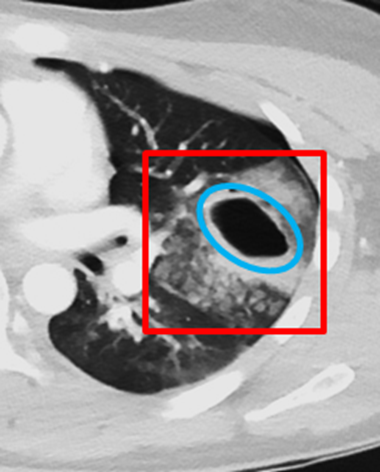

Additional Imaging:

Contrast-enhanced chest CT scans were obtained in the axial, coronal, and sagittal planes for further evaluation.

Quiz 2:

-

What is the most significant finding on the chest CT?

(1) Pulmonary contusion

(2) Subcutaneous emphysema

(3) Pneumohematocele

(4) All of the above

Answer and Explanation:

This patient demonstrates multiple acute findings consistent with those seen on the initial chest radiograph, including left-sided multiple rib fractures and a left pneumothorax. Given the mechanism of acute blunt trauma and the associated rib fractures, the areas of consolidation are most consistent with pulmonary contusions. Axial CT images reveal air- and fluid-filled cystic structures in the posterior aspects of both lungs, consistent with traumatic pneumohematoceles. Additionally, subcutaneous emphysema is visualized along the left chest wall on axial sections.

-

Which of the following should be included in the final diagnosis?

(1) Tension pneumothorax

(2) Large chest wall hematoma

(3) Bilateral pulmonary lacerations

(4) Lung abscess

(5) Post-traumatic tracheobronchial dissection

(6) Ruptured breast implant

Answer and Explanation:

In the setting of high-energy trauma, pulmonary lacerations should be strongly considered. These occur due to rupture of the alveolar walls and surrounding lung parenchyma, creating cavities filled with air (pneumatocele), blood (hematoma), or both (pneumohematocele). In this case, bilateral pulmonary lacerations are evident: on the right, likely due to shear forces against the vertebral bodies; and on the left, likely due to direct puncture from fractured ribs—together forming a classic pattern. Subsequent development of traumatic pneumohematoceles is observed.

Other options listed are not supported by the current clinical or imaging findings.

Findings and Diagnosis

Imaging Findings:

Radiograph: Multifocal airspace opacities were noted in the left lung, adjacent to sites of acute rib fractures. A small to moderate left pneumothorax was also identified.

Contrast-enhanced Chest CT Findings:

There are displaced, comminuted, and non-displaced fractures of the left 5th through 8th ribs. Associated findings include subcutaneous emphysema within the left chest wall, a left-sided hemopneumothorax, and bilateral pulmonary contusions. Multiple bilateral post-traumatic pneumatoceles containing air-fluid levels are noted, with the left-sided lesion showing perilesional hemorrhage, suggesting a traumatic etiology.

Differential Diagnosis:

-

Pulmonary laceration

-

Pulmonary contusion

-

Pulmonary hemorrhage

-

Pulmonary infarct

-

Congenital cystic adenomatoid malformation (CCAM)

-

Cavitating pneumonia

-

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA)

-

Rheumatoid nodules

Final Diagnosis:

Pulmonary Laceration

Discussion:

Pulmonary Laceration

Pathophysiology:

Pulmonary laceration most commonly results from severe blunt thoracic trauma, penetrating injury, rib fractures, or inertial deceleration forces, leading to tearing of the pleura and lung parenchyma.

These injuries result in air-filled (pneumatocele), blood-filled (hematoma), or mixed air-fluid cavities (pneumohematocele) due to rupture of alveolar walls and disruption of pulmonary architecture. They may become apparent immediately or in a delayed fashion following the injury.

-

Lesions typically range from 2 to 5 cm, but can be larger.

-

Characteristically, they are thin-walled and spherical or ovoid, shaped by the elastic recoil of lung tissue.

-

Pulmonary lacerations may persist for weeks, months, or even years, potentially resulting in parenchymal scarring.

-

Radiographic detection may be delayed, depending on lesion depth and associated findings.

-

Lacerations are classified into Types I–IV, with Type I (compression rupture) being the most common.

Epidemiology:

-

Children are more vulnerable due to increased thoracic wall compliance.

-

The incidence of pulmonary laceration in blunt thoracic trauma ranges between 4.4% and 12%.

-

Deep lacerations account for approximately 50% of hemothoraces.

-

Up to 50% of lacerations may be missed on initial chest radiographs.

Clinical Presentation:

-

History of blunt thoracic trauma

-

Pale, clammy skin

-

Hemorrhagic shock

-

Bright red hemoptysis

-

Progressive hypoxia

Imaging Features:

Chest Radiograph and CT:

-

Heterogeneous lucency representing air-filled cavities

-

Pneumothorax and hemothorax often coexist

-

Associated findings may include:

-

Pulmonary contusion: ill-defined consolidation or ground-glass opacities

-

Rib fractures

-

Pulmonary hemorrhage

-

Small nodular opacities representing residual hematomas

-

Treatment and Prognosis:

-

Hemorrhagic shock is associated with poor prognosis and may have mortality rates up to 30%.

-

Supportive care is appropriate for clinically stable patients.

-

In unstable cases, chest tube drainage, mechanical ventilation, bronchial occlusion (for endobronchial bleeding), or surgical intervention such as emergency thoracotomy or lobectomy may be warranted.

(1) Dumper

J, Mackenzie S, Mitchell P, Sutherland F, Quan ML, Mew D. Complications of

Meckel's diverticula in adults. Radiographics. 2013;267(1):251-255.

(2) Federle

MP, Jeffrey RB, Woodward PJ, Borhani A. Diagnostic Imaging: Abdomen. 2nd ed.

Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2009:135-139.

(3) Moots

PL, O'Neill A, Londer H, et al. Preradiation chemotherapy for adult high-risk

medulloblastoma: A trial of the ECOG-ACRIN Cancer Research Group (E4397). Am J

Clin Oncol. 2018;41(6):588-594.

(4) Pediatric

x-ray imaging. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) website. https://www.fda.gov/radiation-emitting-products/medical-imaging/pediatric-x-ray-imaging.

(5) Pipavath

SN, Godwin JD. Acute pulmonary thromboembolism: A historical perspective. AJR

Am J Roentgenol. 2008;191(3):639-641.

(6) Wallace

RJ Jr, Griffith DE. Antimycobacterial agents. In: Kasper DL, Fauci AS, Longo

DL, Braunwald E, Hauser SL, Jameson JL, eds. Harrison’s Principles of Internal

Medicine. 16th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2005:946.

Comments

Post a Comment